Reciprocity Failure

‘Reciprocity Failure’ explores tensions between modernity, the divine, and the nuances of power, through architectural space, religious monument, and the symbolic divisions between analogue photography, painting and contemporary digital media.

In analogue photography there is an inverse and reciprocal relationship between the intensity and duration of the light falling onto light-sensitive materials, which remains constant throughout typical photographic conditions. Reciprocity failure refers to the inability of the two exposure variables to behave in a reciprocal fashion as the relationship breaks down at very high or very low light values. The breakdown of reciprocity is utilised, in this project, as a metaphor for our lived experience of the promises, and consequent failures, of Modernity and progress. The seemingly random juxtaposition of elements in this grouping are linked through intersecting histories of towers, bells, air travel, firefighting and religion…all playing their role in defining Modern life.

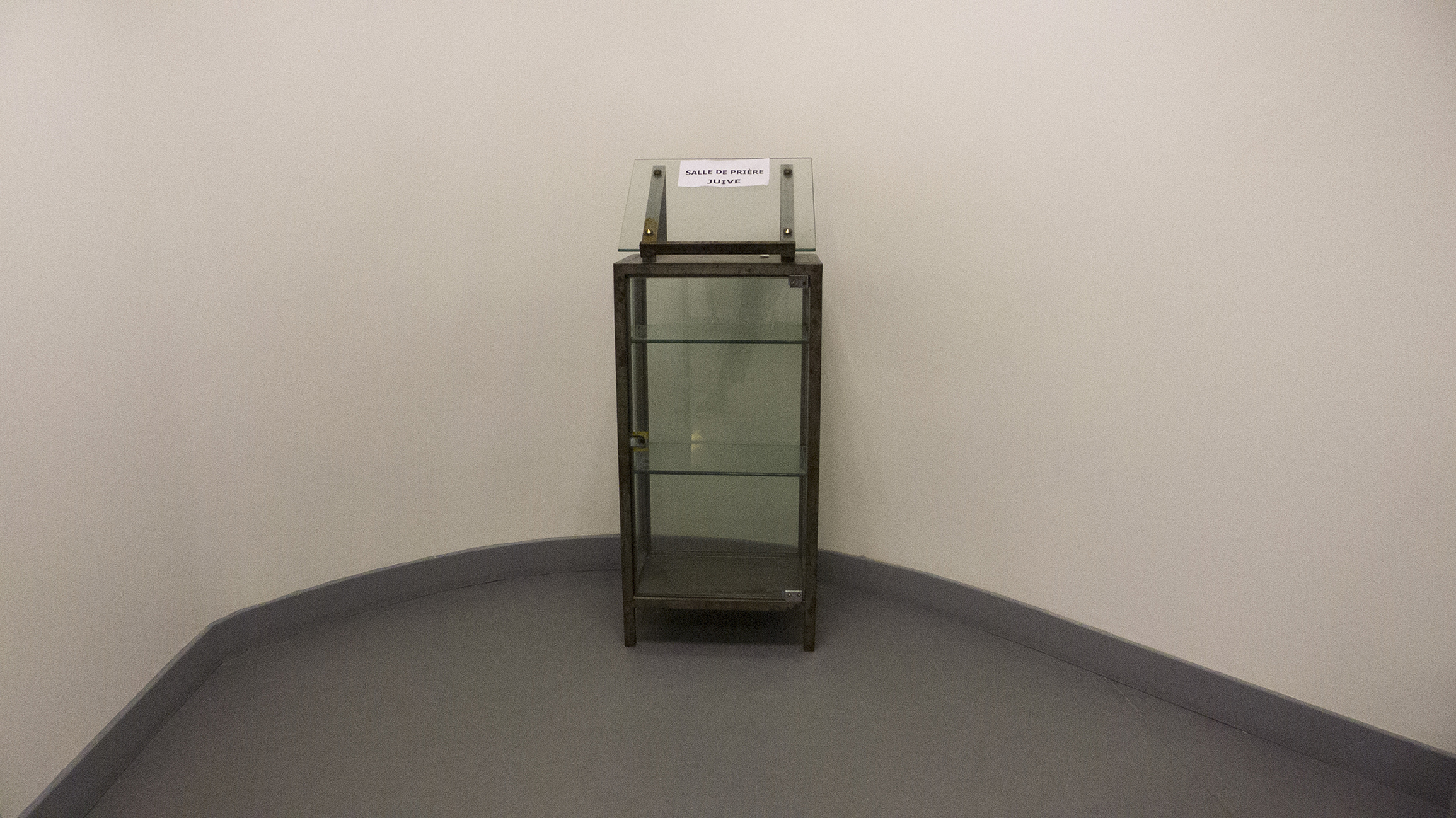

In Johan Grimonprez’s film-essay D-I-A-L History, about the struggle between history and spectacle in the 20th century he posited the airplane as a symbol of historical progress and spectacular horror. Airport prayer spaces are utilitarian monuments to a lived disconnect between the divine and the Modern. Potentially anachronistic, awkward sites of anxiety within the shiny palaces of modernism. Possible quiet sentinels to the failed promises of progress or charged vestigial spaces mocking technological futures whilst acknowledging the airplane as a duel symbol of historical progress and spectacular horror.

Air traffic control towers oversee landing strips and their attendant architectures. They embody the title of the Richard Brautign poem and subsequent Adam Curtis’s film “All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace”. Control towers exemplify benevolent surveillance and benign panopticism, as the Modern exerts its control through all-seeing architecture.

There is a drill tower located in nearly every London fire yard. Many of them were built in a similar era which appears to parallel the rise and designs of social housing in the UK. They are incongruous secular towers looming over housing projects and high streets. The fire station practice staircases escape the internal structural logistics of the sentinel, the defensive, the grandiose and the metaphorical. The height does not depend on the size of the domain that they command, the top is no vantage point and the architectural style simply mimics the stairs of the homes they hope to save.

These drill tower paintings are a memorial to the ten fire stations closed in the mid 2010s by Boris Johnson during his mayorship of London. Of the ten London fire stations closed at least five were of the older early 19th century redbrick variety which are all now being redeveloped as luxury private apartments.

Historically the tower, whilst having had a role in fortification, capitalist aggrandisement and surveillance is also closely allied with the architecture of the divine. Minarets are referred to as the gates of heaven and earth and are ideal vantage points from which to call to prayer. Towers contain bells, which communicate the will of the divine to a broad regional audience. The bells are often restrained within these towers by complicated mechanics of wood, rope and metal as if their magical power would be uncontained without these archaic wooden structures. Commissioned paintings by Michel Lafleur from photographs by Leah Gordon

In ‘La-Bas’ by J-K Huysmans the character Carhaix entreats, “There is only one word in everyone’s mouth: progress. Progress for whom? Progress for what?” and the bell becomes a symbolic cypher for that which is left behind. “Bells have had their day; or, if not the bells, then the bell-ringers themselves! It is a profession, like so many, which is dying out: charcoal-burners, roof-thatchers, stonemasons, firemen of the old school.”